|

|

Excerpts from ARTISTS AND MENTAL ILLNESS: GOING TO THE HOSPITAL, GOING TO THE ARTISTS' COLONY

©Ann Starr

The James Campbell Distinguished Lecture Rush

Presbyterian St. Luke's Medical Center, Chicago

Delivered on 26 January 2000

What an unfortunate title for Dr. Kay Redfield

Jamison's book about artists and bipolar disorder:

Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the

Artistic Temperament. "Touched with fire?" Excuse

me? Shouldn't that be Burned Alive? I am a visual artist

with manic-depressive illness. I have never felt myself

"touched with fire," or visited by any gods. I am more

likely to feel incinerated. As with the trash.

Dr. Jamison impressively lists in Appendix B many artists

who suffered (nota bene the simple past tense; none

suffer in the present) bipolar illness. She notes with an

authoritative variety of daggers and bullets (not by

accident are they collectively called dingbats) who is known

to have been hospitalized, or to have attempted suicide, or

to have succeed in the effort—that is, in an effort no one

could ignore or mistake. Did Janis Joplin commit suicide by

pursuing drugs and a tormented life in the fast lane?

Jamison tends to prefer the straightforward, like Sylvia

Plath and her definitive, pilot-lit way out.

Jamison's fascinatingly wide-ranging—and undated—list of

artists to whom she attributes bipolar disorder includes

people from historical periods and cultures with a variety

of points of view on idiocy, religion, illness, inspiration,

and brain disease. She includes Michelangelo (fifteenth

century: 1475-1564). There is John Bunyan (1628-1688) in

there along with Robert Burns (1759-1796); everyone's

favorite madman, Vincent van Gogh lived from1853-1890, and

Anne Sexton form1928 to 1974. While we know next to nothing

about some and have well-documented biographies of others,

all are diagnosable in the interest of a theory today. It's

an interesting study in anachronistically applied terms and

concepts at least.

Whether or not those folks were bipolar, I am interested

that the tormented Joplin is missing, as are Jimi Hendrix

and Kurt Cobain. Not only are there no artists noted from

popular culture, but entirely absent are landscape

designers, architects and engineers, graphic artists,

weavers, set designers, aesthetic surgeons and

orthodontists, quilters, disc jockeys, actresses who wait

tables and await roles, photo journalists, cooks and bakers,

or city planners. And what about authors whose excellent

fictions have not appeared during decades of retrenchment in

publishing? I'll leave to someone else the mathematicians,

physicists and botanists, whose "creative temperaments

certainly inform their work.

Oh no: could they possibly be artists too?

Well, of course not. For the purposes of research, the

Artist is always someone both dead and immortalized within

the most conservatively-construed genres. Their work hangs

in the Prado, is heard at Alice Tully Hall, or is taught

from a Norton Anthology of a western literature. The

definition of artist is exclusive and romantic.

Real artists have widely-acknowledged reputations and

universally acknowledged death certificates. Like most

living artists, I will remain unacknowledged for the

research record.

When I meet a new psychiatrist, they ask questions born

of such authority-born skepticism, questions like these:

"So you are an Artist? What kind of art do you make?"

As if this will clear it up. What they want is not what I

do or how I think, but if I paint on velvet.

Next, "Where is my studio?" ("At home" would be sufficiently

damning, but I trump that because I don't even have a

studio. I work when I can earn space at artists' colonies,

the existence and purpose of which institutions doctors know

nothing of.)

Third question: Do I show my work? (In fact, I exhibited in

thirteen shows across the country last year and in fourteen

the year before. Why should a psychiatrist know the Center

for Book Arts or any of the other galleries and museums I

show in?)

On top of it all, I have no more training as an artist than

two audited drawing courses at a liberal arts college, and

one life-drawing class I paid for at an art school.

But the point of all these questions is, "Are you a real

artist?" with their expected conclusion that I am not

because no one has ever heard of me. Obviously, no one wants

to be taken in by the claims of a nut, and psychiatrists

screen for symptoms like grandiosity. But it's a

disingenuous question anyway since most doctors appear to

believe, like Jamison, that real artists are dead artists,

or are well accounted for in the press.

Artists, like psychiatric patients, are potential tricksters

because our roles are not easy to identify. Few are lucky

enough to pursue art full-time. I have been challenged in a

therapy group (not by the doctor, I admit) by the

proposition that I am merely a "frustrated housewife who

paints." That I am a frustrated housewife is absolutely

true. It in no way precludes the fact that I am an artist—a

real, live artist afflicted by manic-depressive

illness that can thwart her work from time to time.

Few recognize either that mental illness is rarely a

full-time, whole-consuming occupation. People who live

neither as an artist nor mentally ill person rarely have the

imagination to conceive of concentrated or heightened states

of mind as other than actively threatening to them. It too

rarely occurs to people that mental illness affects the

afflicted, who, like everyone else, would like to get on

with their lives and work as well.

—

Jamison cites many types of studies concluding that

artists are unusually prone to be bipolar, thus linking

bipolar illness and "the creative temperament." Perhaps,

then, bipolar illness is integral to the artistic process?

But Jamison also demonstrates that of all the major

psychiatric diseases, bipolar illness is more likely than

any other (schizophrenia included) to result in suicide.

What have we got in this extraordinary package of suicide

and creativity?

I know that for any person harboring suicidal thoughts, to

remain alive requires substantial strength and creativity.

This is a point worth making very, very clearly: Duration is

the most common presupposition in life. But it is an

assumption, and it can be belied. For the suicidal

person, creativity is not light bulbs illuminating overhead.

This creative force—the sorely challenged life force—goes

under the condescending popular terms of "willpower," or

"grit," stubbornness, or even orneriness. But the effort to

keep life together is the supreme creative effort, however

miserable or degraded the forms it takes may appear to

bystanders.

As a manic-depressive person, first I survive. Everything

else requires creativity of a much less demanding order.

I include among the lesser tasks such central ones as my

need to create—out of and apart from my own horrors—a

wholesome place for my family. Important, too, but less than

survival, is trying to imagine into existence a life for

myself, where the core rot is halted, maybe even

repaired a little. A little farther down the line, I do the

things artists are thought to do.

Against all this, manic-depressive illness is a big overlay.

It is the constant threat to my life. This is not an

inspiring illness; quite the opposite. It stresses a finely

tuned and perceptive person to literally intolerable

excesses of emotion. It is the rack. Mania can so urgently

require abatement that only three things can relieve it: the

dumbest depths of comatose depression, heavy and consistent

intake of medications (include drugs and alcohol here), or

suicide. There is no art making in these circumstances. I

make art between psychiatric episodes, and despite them.

My pain is partly generated by—and is focused by—the

pattern of life bipolar illness forces upon me. When my work

is about the illness, it is about it in this way: I can see

nothing without seeing it. It is like cataracts, or

hallucinations, imposed upon one's vision. During an

episode, I am reduced to a single-issue life. I have to keep

body and soul together. Then there is no work but

self-protection, which is one experience I believe art can

never express. Art may provide a means of reflection or

therapy for some, but a person deciding whether to live or

die has no other decision to make.

Let me offer another way to see the interconnections between

being an artist and being mentally ill, specifically,

bipolar. In different locations, one can see oneself in

different perspectives. My illness has taken me to an

institution for mentally ill people: I have been an

in-patient on a locked ward of the psychiatric hospital

several times in the past six years. Throughout the same

period, I have also been a resident for several periods of

two weeks or more at art colonies, where artists may go to

do their creative work without constraints or interruptions.

Although it sometimes feels like it, you don't have to apply

to get into the hospital; for colonies you do. Sometimes you

are accepted, sometimes not. When you leave the colony

though, it's on a schedule you've pre-determined; when you

leave the hospital, you are shown the door.

From CONCLUSIONS:

Some creative urge can be found in every person, no

matter how dull or thwarted the life. Unfortunately,

expression of individual creativity can be impeded forever,

like the acknowledgment and expression of emotion can be.

There are good reasons to compare exploring one's creativity

with undertaking a regimen of self-reflection or

psychotherapy. In both, there is much delight to gain

through release of imagination and gain of insight; but

there is a lot of room for uncontrolled, terrifying

discoveries too.

I think that many people sense their own creative

temperaments, but are no more willing to put them to work

than to pursue psychotherapy: Too risky! This point might

give us some perspective, then, on the amount of simple, raw

work done by people who suffer mental illness yet continue,

on top of it all, to be artists. It takes courage to keep

exploring life's open questions, daily, at the most personal

level as well as through art-making.

I never chose to be mentally ill, but I am. I can, however,

choose to mitigate the effects my illness has on the rest of

my life by undertaking a rigorous individual therapy, taking

my drugs as prescribed, going to the hospital if I am

suicidal, and by continuing to go to the colonies

where both my art, my health, and even my ability to lead

daily life are served.

Did I choose to be an artist? Yes and no. It's a calling,

not a job. If I call myself a "professional artist," it

doesn't mean only that I wish to make the money I don't from

my labors. It means that I will pay the price for my

decision: the challenges from others, the delayed rewards

and gratification, the likelihood I will not find a

substantial audience for my work.

People like Kay Redfield Jamison can get away with

romanticizing artists with mental illness because, as a

psychiatrist and sufferer herself, she understands that pain

is central to both the work of art making and the work of

being alive and fully human. In linking the artist to

mental illness, however, she becomes an apologist for

everyone who recognizes a creative urge but fears the

consequences of acting upon it.

There are real rewards for pushing one's creativity hard,

but there are also many uncertainties and bitter

disappointments. Link the artist with something like bipolar

disorder and you get not only "obvious" reasons for failing

to use one's own creativity, but a subtle way to transfer

fear and hostility to those who do—to those whose efforts

may challenge you or make you uncomfortable for your

inability to stretch farther.

One durable characterization of artists in our culture is

that they are bizarre, irresponsible, immoral, or

anti-social people. Mental illness is a handy catchall for

any number of unusual or uninterpretable traits. For the

socially insecure, being artistic isn't a compliment: "I'm

not mentally ill; no muse is visiting me. I may not be an

artist, but at least I am unquestionably sane." The artist

becomes the cultural "carrier" of a dreaded condition with

agreeably ill-specified symptoms that are diagnosable by any

person who nominates him- or herself as 'normal.' Any artist

can be the suspicious object of fear, admired—if at all—only

in quarantine.

THE BODY INSIDE ME

© ANN STARR

Northwestern University Medical School, 1999

Addressed to an audience of medical students and

physicians and subsequently

revised for the Barnard Feminist Art and Art History

Conference, October, 2000

Let's start by remembering that the artist, scientist,

and doctor once existed in the same person. Once, the

connection that I assume between observing, drawing, and

knowing was taken for granted. Once, too, anatomy was

completely new to the eye and the hand. The Renaissance and

its explorers opened many continents only posited by ancient

imaginations. Then, somewhere along the line, the doctors

and the artists got separated.

Gross anatomy is no longer a field of primary discovery.

While you medical students may explore an individual

cadaver, many of your "discoveries" are precedent

certainties planted by lecturers and lab instructors,

confirmed by atlases and Grant's Dissector. Early on in my

medico-artistic explorations, an anatomist friend deflated

my novice enthusiasm by telling me that a new muscle had

been discovered in the jaw a few years ago. So much for

romance.

Like most artists, my first body explorations came in a

life drawing class. Many artists proceed to take not only

life drawing but also anatomy for artists. They are

introduced to the skeleton and superficial muscles as a way

of improving their renderings of the exterior.

You get (dead) cadavers; we get flexible,

posing models. Both sorts of specimens create high emotion

in the learners, emotion that must pique students and which

necessitates firm boundaries in our responses. Another

similarity is that cadavers and models share a certain

self-selection principle. But while I gather that people of

many looks and histories commit their bodies to medical

education, the models who commit themselves to artists are

generally—not always, thank heavens—the young, lithe, and

beautiful. The art of the figure is thought to glorify human

beauty. Rarely drawn in art schools are dwarfs, elderly

persons, cripples, or obese people. An essentially Vitruvian

aesthetic still dominates, idealizing proportion.

Models' bodies are artists' basic training, as cadavers

are for you. The more one draws the body, the better one

knows it and can use it to convey one's own subjects and

meaning. Models have ceased to be necessary for me. My

real work is not rendering, any more than yours will be

identification of tendons.

My own drawing has never been without high emotional

content. For me, the body is emotion, feeling,

passion, disguise and revelation. I've come to draw and

paint the body almost exclusively for all of the intense

content that you are being trained to handle with the utmost

control. As my drawings elongate the curve of a back, or

express themselves in a tumult of twists, I call forth the

attractions and fears you will have to suppress in order to

work at all. They're all there, though: All the time.

You are learning not to respond overtly to the sexuality,

beauty, exposure, grief, or grotesquerie of the body. Like

every human, you will know it profoundly nevertheless. No

less than I, whose business is expression, you will never be

free from it.

Now, interestingly enough, when it comes to the

interior of the body, the whole picture changes. This is

considered your exclusive domain: Initiation is emphatically

required. Where the naked body is culturally the locus of

infinite passion and fantasy for everyone, the interior

elicits very few, and almost entirely fearful responses. We

non-doctors shun it. To look inside the body is to face

death; it is absolutely taboo for everyone—except for you.

You are entering what our culture has made almost literally

a priesthood. Your ability to do and survive this remarkable

looking is your source of power. You neither die nor grow

ill nor poison the rest of us as a result. We in the laity

are happy to have you do it. We would not.

At least, most of us wouldn't. But I would. I hope I can

explain this naturally occurring oddity.

My career drawing the figure reached an impasse a few

years ago. These two slides show some of my last full-figure

drawing. For these I hired models. They moved continually as

I drew, recording their cores and limbs in motion, as a way

of pressing, pressing to express the excitement and emotion

of the body, virtually dissolving the flesh in the visual

record of the action. Such difficult work it was, and such

emotional intensity in the act of drawing.

Now, I will allow that the emotional intensity is

conveyed by these records; but it is certainly legitimate

for you or any audience fail to see that the body is in

these drawings. But I didn't like it that the passion was

spinning out of the flesh. Feeling is integral to bodies and

I am not interested in abstracted, but in located emotion.

So, is it possible to isolate this location without words?

If so, where can I find it?

If human—as both emotion and sensation—inheres in the body,

how can I convey its depth, force, and complexion without

resorting to time-worn visual tropes? No artist works

unburdened by what others have done. The nude is highly

eroticized throughout history, and there's no dismissing

that. Bones, including the skull, have been reduced for

centuries to simple emblems of death—it would be almost

impossible to get them to carry any other significance. And

exposed sub-cutaneous flesh implies violence. So, all in all

this makes for a very limited emotional palette despite the

body's obvious richness. Isn't there something between the

limitations of representational conventions and the

multifarious, problematic experience of actual flesh?

Well, there are symbols—as in this small drawing, "The

Group." In this piece it is impossible to distinguish the

"figures" from the "chairs." The furnishings offer another

way to reveal the emotion in the figures. It also allows a

way to work past the associations viewers are ready to make

with people's state of dress or undress, so the content I'm

interested in isn't obfuscated by associations with either.

This image of a cross, is another way to draw the figure

symbolically; and this next image, with its surreal grouping

of figures uses fanciful distortions of human form as a way

to convey a crowd of emotions.

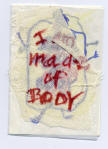

But in this drawing, "Eureka Portable," I really began to

get the idea. (Eureka portable being, for those of you still

innocent, a small canister-style vacuum sweeper.) The figure

is represented symbolically, but its own parts

constitute the symbol. The uterus, vagina, full lips and

little-girl dental gap add up to the object-person. The

emotion is not conveyed by a vision of an objectified

exterior, but by the subject's own guts—her emotion

is inside and reveals her feelings about her objectified

presence in the outside world.

Eureka, indeed! It has been ever since as if the organs,

the interior cavities and body's byways were my very own

discovery—as, of course, they are! To find that there is so

much of a body still to explore and work with, so much that

is not pre-charged with convention. Deep inside there is a

world that does not come first to the eye—to think of it

plunges us into real terra incognita, to be explored

through imagination and the levels of fantasy we must work

hard to eke to the surface.

Now, I say that none of what we experience inside is ever

known visually. That's not true, because medicine sees this

every day. That's a huge exception. I have already alluded

to the taboos about the interior and the need we all have to

avoid looking at it directly. As I mentioned, a sine qua

non of medicine is to objectify and distance in order to

make bodies treatable and tolerable for doctor-humans as

well as for the rest of us.

Because of medicine in general education, all of us know

what the various organs "look like." I think, though, that

anatomical imagery does more than record and inform: it

protects us all, too. Radiology, medical illustration—even

the fact that we are still satisfied with the world view

implied in the elegant Vesalius—suggest that we are

contented with the boundaries that the conventions of

medical representation provide. But I want to suggest this:

There is no a priori reason that medicine's be the

only way to pictures organs. Why must all expression be

distilled away from representations of the interior?

It took no little doing for me to achieve access to human

organs for my observations, but in 1995 I finally got my

first chance. Among my questions, I wondered, "Do

human organs look like their representations?" If I, an

untrained observer, draw the material a medical illustrator

does, how would our renderings compare? What's there that

the "trained" draftsman doesn't see that I can? What

does a heart look like if you see it without names and

anatomical study to guide you? The lack of medical

vocabulary allows my vision to settle where it will—on form,

emotion, or non-corporeal associations, as quickly as yours

will trace the venous system or evidence of an anomaly.

What, for that matter, do anatomical anomalies even mean for

me? Am I to identify them as oddities, or simply as

corporeal events?

|